Alright, so we pump energy into a chaotic system and obviously the extremes will get more exteme. Stronger hurricanse, colder hurricanse and snap freezes, deeper floods, wet bulb events further north than you think possible, whatever. This is the known unknown.

I am existentially afraid of the unknown unknowns. At what point do the phytoplankton I’m currently breathing the poop of have a mass extinction event? All of human civilization is about to drown on dry land and I spend 5 days a week maintaining software that charges people for turning on their lights.

I crave death I crave oblivion death to america death to capitalism death to me.

If you’re familiar with the neuroscience research on dementia, you’ve maybe heard people talk about “cognitive reserve.” The basic puzzle is similar: we have a good understanding of what the organic basis of dementia is, but it turns out that two people can have similar levels of organic degradation–brain damage–but show markedly different levels of actual functional cognitive decline; one person might be barely self-sufficient, while the other shows almost no symptoms, and their brains look basically identical. Cognitive reserve helps explain this: if you’re educated, otherwise healthy, used to thinking critically and reasoning out problems and so on, you can absorb more organic damage without loss of functionality.

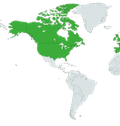

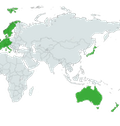

In climate policy discussions, we talk about something similar called “adaptive capacity.” This has a ton of overlap with wealth, but even more so with the kinds of material conditions that Marx talked about just through the lens of climate change. Adaptive capacity is, as you might expect, the set of material conditions that make it possible for a country (or city or region or continent or whatever) to absorb climate change without people starving, or supply chains breaking down, or other harmful impacts becoming super significant: it’s a kind of socio-economic cognitive reserve. If your economy is primarily agrarian, has a weak social safety net, is relatively poor, is mostly coastal (or already quite warm) or otherwise already eeking out an already marginal existence, even a small climatological shock has the potential to wildly destabilize things to the extent that it’s impossible to recover from.

On a household level, this looks like the poverty trap. Consider two households: one is barely scraping by, and the other makes $250,000 per year. When they’re both subjected to an economic shock, what happens? Both see their incomes and resources depleted, but the rich household has enough assets that they can absorb the shock wait for a recovery, and come out the other side fine. The poor household doesn’t have this luxury. If the shock is something like (say) a medical emergency, maybe the household has to sell their only car to help pay for the ambulance ride. Without a car, they have trouble getting to work, so eventually they lose their jobs, causing them to get evicted, making it harder to get a new job, etc. We’re all familiar with this kind of material death spiral.

Adaptive capacity is like that on a national level, and that’s why the global south is going to get hit harder by climate change, at least at first. Of course, the negative repercussions aren’t going to be confined there–no matter how much cognitive reserve you have, enough damage will eventually result in dementia. Moreover, things like refugee crises caused by the rolling catastrophe sweeping across the global south will eventually hit the

. It’s eventually going to be bad for all of us but, like most things, it’s going to be worse (and hit sooner) for the people who have already had their resources systematically plundered in order to give the United States more adaptive capacity.

. It’s eventually going to be bad for all of us but, like most things, it’s going to be worse (and hit sooner) for the people who have already had their resources systematically plundered in order to give the United States more adaptive capacity.

Thank you for the explanation