- cross-posted to:

- technology@lemmy.world

- cross-posted to:

- technology@lemmy.world

Once upon a time, typing “www” at the start of a URL was as automatic as breathing. And yet, these days, most of us go straight to “hackaday.com” without bothering with those three letters that once defined the internet.

Have you ever wondered why those letters were there in the first place, and when exactly they became optional? Let’s dig into the archaeology of the early web and trace how this ubiquitous prefix went from essential to obsolete.

Where Did You Go?

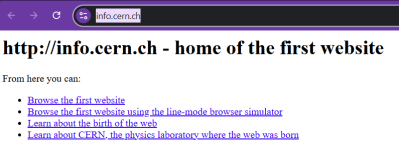

The first website didn’t bother with any of that www. nonsense! Credit: author screenshot

The first website didn’t bother with any of that www. nonsense! Credit: author screenshot

It may shock you to find out that the “www.” prefix was actually never really a key feature or necessity at all. To understand why, we need only contemplate the very first website, created by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN in 1990. Running on a NeXT workstation employed as a server, the site could be accessed at a simple URL: “http//info.cern.ch/”—no WWW needed. Berners-Lee had invented the World Wide Web, and called it as such, but he hadn’t included the prefix in his URL at all. So where did it come from?

McDonald’s were ahead of the times – in 1999, their website featured the “mcdonalds.com” domain, no prefix, though you did need it to actually get to the site. Credit: screenshot via Web Archive

McDonald’s were ahead of the times – in 1999, their website featured the “mcdonalds.com” domain, no prefix, though you did need it to actually get to the site. Credit: screenshot via Web Archive

As it turns out, the www prefix largely came about due to prevailing trends on the early Internet. It had become typical to separate out different services on a domain by using subdomains. For example, a company might have FTP access on http://ftp.company.com/, while the SMTP server would be accessed via the smpt.company.com subdomain. In turn, when it came to establish a server to run a World Wide Web page, network administrators followed existing convention. Thus, they would put the WWW server on the www. subdomain, creating http://www.company.com/.

This soon became standard practice, and in short order, was expected by members of the broader public as the joined the Internet in the late 1990s. It wasn’t long before end users were ignoring the http:// prefix at the start of domains, as web browsers didn’t really need you to type that in. However, www. had more of a foothold in the public consciousness. Along with “.com”, it became an obvious way for companies to highlight their new fancy website in their public facing marketing materials. For many years, this was simply how things were done. Users expected to type “www” before a domain name, and thus it became an ingrained part of the culture.

Eventually, though, trends shifted. For many domains, web traffic was the sole dominant use, so it became somewhat unnecessary to fold web traffic under its own subdomain. There was also a technological shift when the HTTP/1.1 protocol was introduced in 1999, with the “Host” header enabling multiple domains to be hosted on a single server. This, along with tweaks to DNS, also made it trivial to ensure “www.yoursite.com” and “yoursite.com” went to the same place. Beyond that, fashion-forward companies started dropping the leading www. for a cleaner look in marketing. Eventually, this would become the norm, with “www.” soon looking old hat.

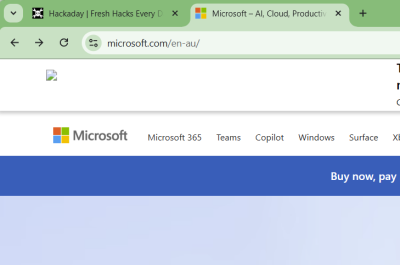

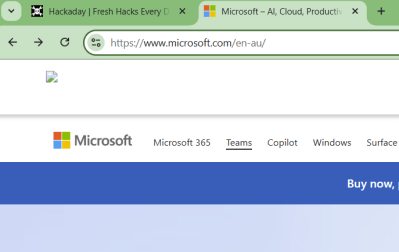

Visit microsoft.com in Chrome, and you might think that’s where you really are… Credit: author screenshot

Visit microsoft.com in Chrome, and you might think that’s where you really are… Credit: author screenshot

Of course, today, “www” is mostly dying out, at least as far as the industry and most end users are concerned. Few of us spend much time typing in URLs by hand these days, and fewer of us could remember the last time we felt the need to include “www.” at the beginning. Of course, if you want to make your business look out of touch, you could still include www. on your marketing materials, but people might think you’re an old fuddy duddy.

…but you’re not! Click in the address bar, and Chrome will show you the real URL. www. and all. Embarrassing! Credit: author screenshot

…but you’re not! Click in the address bar, and Chrome will show you the real URL. www. and all. Embarrassing! Credit: author screenshot

Hackaday, though? We rock without the prefix. Cutting-edge out here, folks. Credit: author screenshot

Hackaday, though? We rock without the prefix. Cutting-edge out here, folks. Credit: author screenshot

Using the www. prefix can still have some value when it comes to cookies, however. If you don’t use the prefix and someone goes to yoursite.com, that cookie would be sent to all subdomains. However, if your main page is set up at http://www.yoursite.com/, it’s effectively on it’s own subdomain, along with any others you might have… like store.yoursite.com, blog.yoursite.com, and so on. This allows cookies to be more effectively managed across a site spanning multiple subdomains.

In any case, most browsers have taken a stance against the significance of “www”. Chrome, Safari, Firefox, and Edge all hide the prefix even when you are technically visiting a website that does still use the www. subdomain (like http://www.microsoft.com/). You can try it yourself in Chrome—head over to a www. site and watch as the prefix disappears from the taskbar. If you really want to know if you’re on a www subdomain or not, though, you can click into the taskbar and it will give you the full URL, HTTP:// or HTTPS:// included, and all.

The “www” prefix stands as a reminder that the internet is a living, evolving thing. Over time, technical necessities become conventions, conventions become habits, and habits eventually fade away when they no longer serve a purpose. Yet we still see those three letters pop up on the Web now and then, a digital vestigial organ from the early days of the web. The next time you mindlessly type a URL without those three Ws, spare a thought for this small piece of internet history that shaped how we access information for decades. Largely gone, but not yet quite forgotten.

From Blog – Hackaday via this RSS feed

There was a campaign in the 2000s to get rid of the now-superfluous www subdomain called “no www”, and you could get a fancy badge for your site if it validated.